Chef and Kitchen Staff Fired After Walkout

On a packed Friday night in December, the kitchen collapsed in real time at a high-end restaurant as diners at Bar Casa Vale watched racialized violence unfold before their eyes.

At around 8 p.m., with the dining room full and tickets still coming in, executive chef Jahquari was physically assaulted by Bar Casa Vale’s assistant general manager Sarah Carlisle in the open kitchen. Minutes later, Jahquari and his entire back-of-house team walked out.

By the next day, every single one of them was fired.

What management framed as a childish walkout was, according to multiple workers who witnessed the incident, a collective response to workplace violence, racialized mistreatment, and an industry culture that treats kitchen labor as disposable, especially when that labor is Black, brown, immigrant, or working class.

Jahquari had been the executive chef at Bar Casa Vale, a higher-end Spanish restaurant in Portland, Oregon since July 5th. “I’ve been working over 100 hours a week, 7 days a week since I started.” On December 12, during a busy Friday night service, he says he was confronted by the assistant general manager over a plating decision.

“She starts telling me I can’t do this, that I’m embarrassing her,” Jahquari said. “And then she grabs my arm, grabs my shirt, and tells me I’m coming outside with her.”

Jahquari pulled away and refused. The assistant general manager left the kitchen and called Jess Hereth, the general manager, who arrived shortly after. Rather than addressing the physical assault, management told Jahquari to "keep plating" and that they would “talk about it later.”

For the cooks working the line, that was the breaking point.

“The only reason he stayed was for us,” said one worker. “It was Friday night service. Just weeks before Christmas. We all needed the money. But once we saw what happened, it was like, yeah, fuck this.”

The entire kitchen collected their things, packed up their knife bags and walked out together.

Bar Casa Vale operates with an open kitchen, meaning diners were only feet away when the confrontation happened.

“The whole restaurant saw it,” said Markus, one of the line cooks who walked out on the job. “There were guests sitting not even five feet away. This wasn’t behind closed doors.”

Paul, another line cook, said the moment the assistant general manager put hands on Jahquari was when customers began canceling orders and leaving. “That’s when people started to walk out,” he said. “They saw it. They heard it.” Despite this, management kept the restaurant open, continuing to seat new customers and telling the kitchen to keep plating food.

“They should have shut it down,” Paul said. “Someone had just been assaulted.” Instead, workers say management treated the incident as an inconvenience, not addressing the violence and racism for what it was.

For Jahquari, the incident didn’t come out of nowhere. “I’m the only Black person in that restaurant,” he said. “I dealt with microaggressions and macroaggressions daily. It was just a matter of time.”

Every front-of-house employee was white, according to workers. In the back of house, Jahquari was the only Black worker, alongside two mixed coworkers. Staff say complaints about racist behavior had already been raised, and ignored.

The week before the assault, a white bartender who had already put in his notice repeatedly screamed at Jahquari during service in front of guests. Despite multiple outbursts, he was not disciplined.

“I have never seen someone scream at a chef like that and not be immediately removed,” one worker said. “Especially in an open kitchen.” When concerns were raised to management and HR, who, workers say, was also the director of operations, the response was dismissive:

“I said, 'This is racist,'” Paul recalled while submitting a formal complaint. “And the response I got was, ‘yeah… I really don’t want to believe that’s true.’” No follow-up ever came. “That was the seed,” Paul said. “Everything after that made sense unfortunately.”

After the walkout, Jahquari received a text asking if he had quit. He responded that he left because he had just been physically assaulted.

The next day, Jahquari and every member of the kitchen staff who walked out received termination emails from the general manager. “We were told not to come back for our stuff, and not to come back to the building” Paul said. “As if we were the dangerous ones, when the violence happened to our chef.”

The assistant general manager who put hands on Jahquari faced no known discipline. WWFU contacted the restaurant to further inquire about this and was repeatedly ignored.

Workers say the message was clear: protecting management mattered more than protecting workers, especially when those workers spoke up about racism, named abuse for what it was, and acted collectively instead of quietly accepting that behavior.

This is textbook retaliation. Walk out after a manager puts hands on a worker? You’re fired. Name racism? You’re “difficult.” Demand safety? You’re disposable.

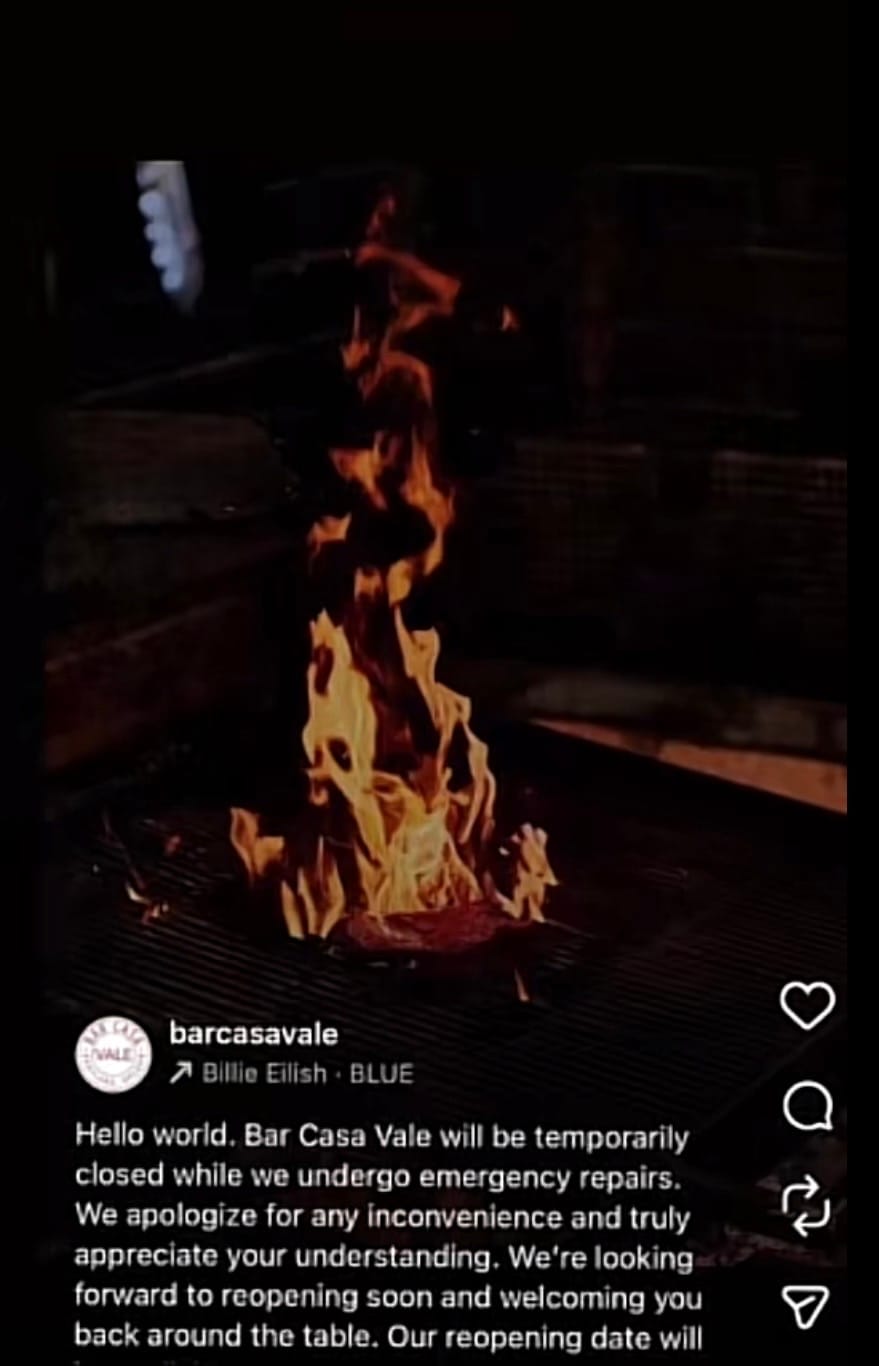

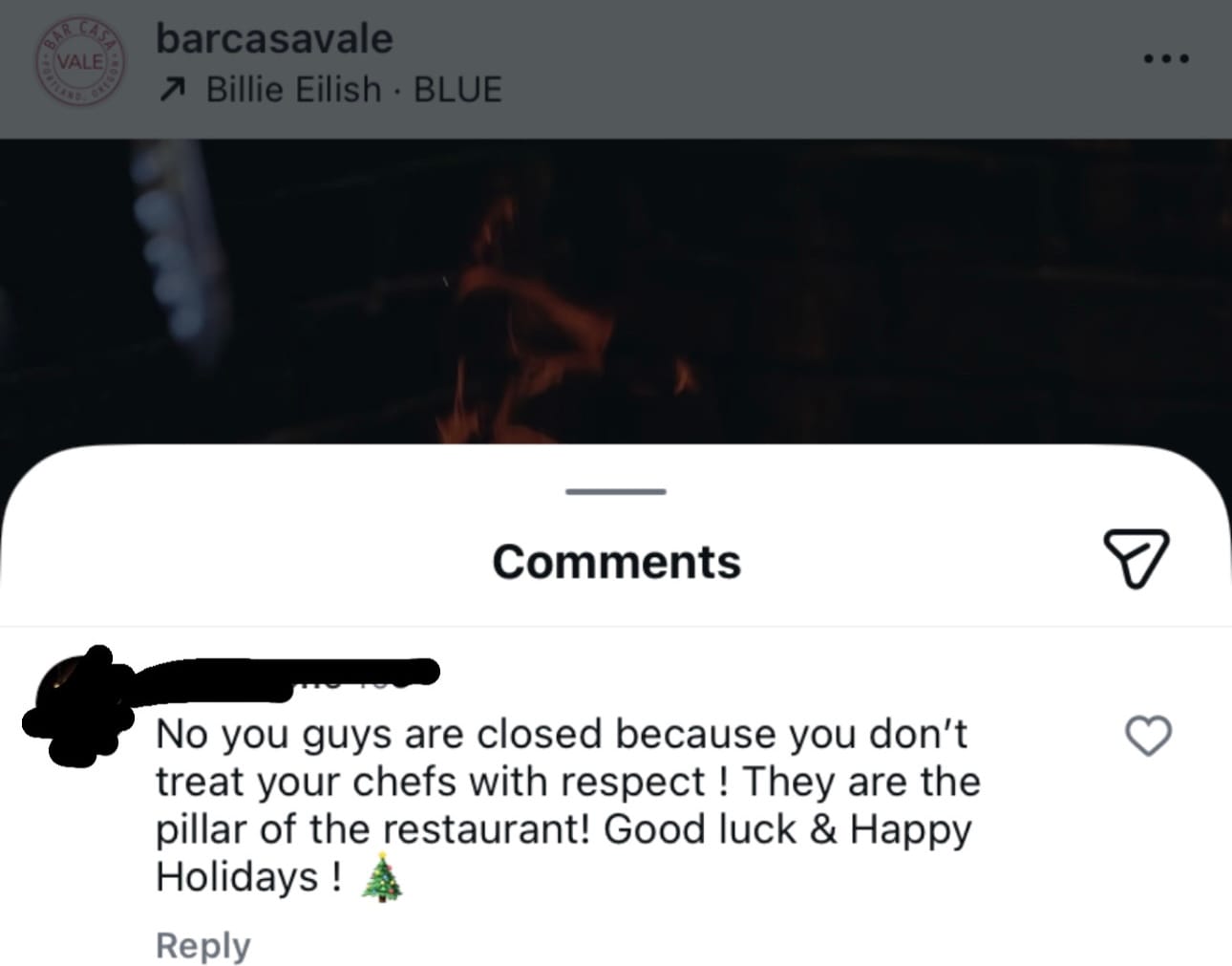

After the executive chef and the entire kitchen staff walked out and were wrongfully terminated the next day, Bar Casa Vale took to social media not to address what happened or take accountability, but instead blamed having to close temporarily on “emergency repairs,” which former workers called out for the lie they said it was. Shortly after making this post, people began calling them out in the comments. The post was then quickly deleted.

While speaking on the decision to walk out of the kitchen and go get a drink with the kitchen crew instead, Jahquari recalled “at the end of the day, it was all bullshit. She put hands on me. At work. And if it was the other way around, best case scenario I would be in jail, and worst case scenario, I would be dead. Point blank period. We’re in Trump’s America, everybody needs to get a fucking grip."

Photos from the pop-up

In the days following their wrongful termination, Jahquari and his former coworkers didn’t retreat quietly. Instead, they organized.

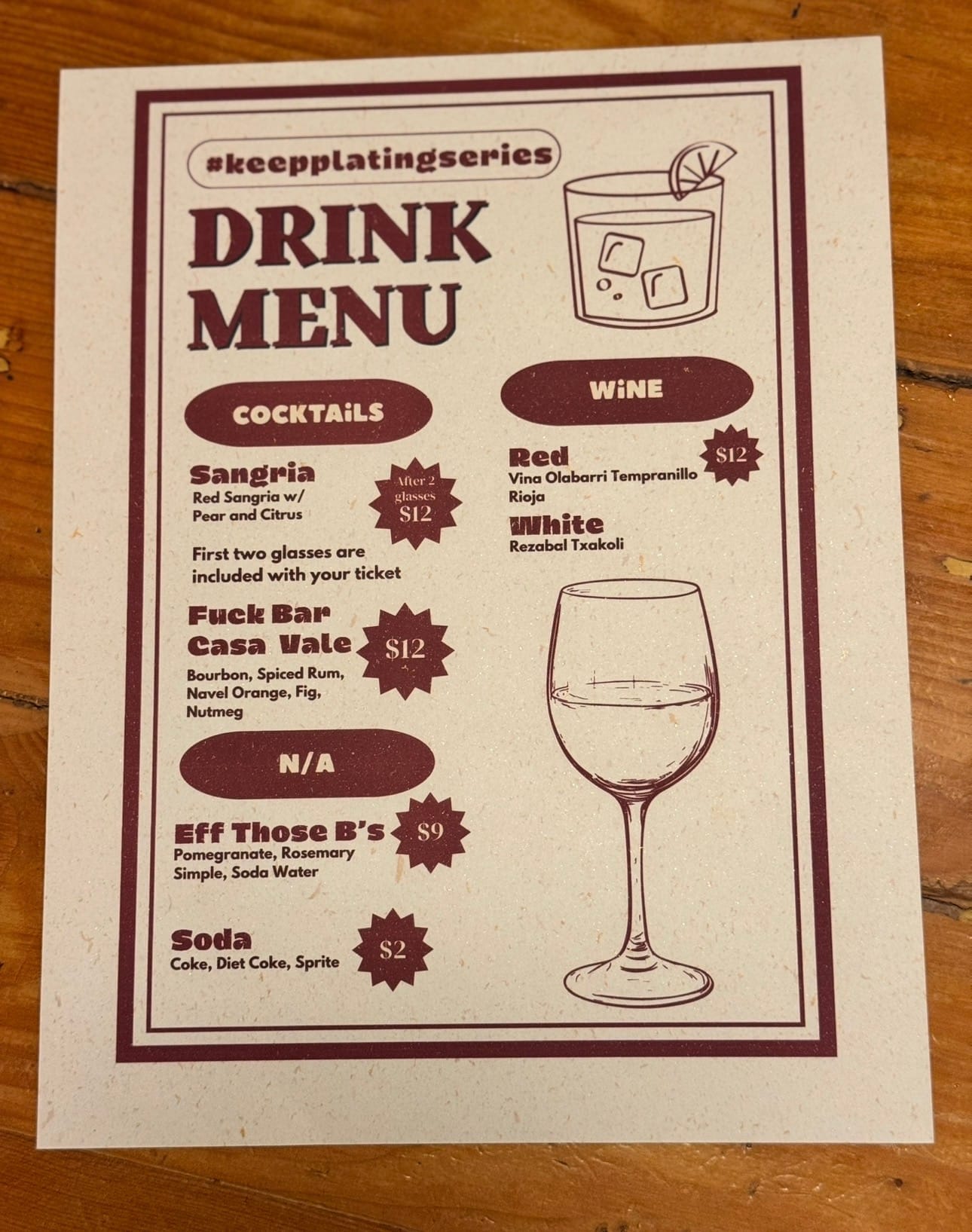

Chef Jahquari and the kitchen staff who walked out with him hosted a paella pop-up, which they referred to as a joyful, defiant act of protest. The pop-up has been called the “keep plating” series, a callback to when the general manager insisted that the chef “keep plating” moments after being assaulted.

“I used to make paella there and nobody gave a fuck,” Jahquari said. “So I decided I’m gonna make it for people who care.”

For Jahquari, the pop-up was both protest and reminder. “Restaurants need kitchens,” he said. “You can’t disrespect and exploit the people doing the labor and expect things to function. The pop-up is in direct protest to Bar Casa Vale and the fact that we were wrongfully terminated. Me and my whole team. Two weeks before Christmas.”

The workers framed the action not just as a response to racism, but to an industry built on exploitation, one that relies on underpaid, overworked kitchen staff while management and ownership extract profit and prestige.

In restaurants, workers are expected to endure screaming, understaffing, unsafe conditions, and abuse as part of the job. Add race to the equation, and the tolerance for mistreatment gets even higher. Especially when the person being targeted is the only Black worker in the room.

“They churn us and burn us,” Markus said. “The ones who actually give a shit are always the ones who get exploited.”

Despite everything, Jahquari insists on joy. “I try to operate from a place of joy,” he said. “That’s the legacy of Black people in this country. We find a way to laugh through everything.” That joy hasn’t dulled the anger, it’s sharpened it.Joy here isn’t about pretending things are fine. It’s about refusing to be broken, isolated, or scared into silence.

Jahquari and the entire team who walked out are continuing to do pop-ups together, refusing to be isolated or silenced, and reclaiming their power.

How to support

Jahquari is organizing future pop-ups with the same crew that walked out alongside him. People can support by showing up, sharing the story, and refusing to spend money at Bar Casa Vale. “If you’re hungry and we’re doing a pop-up,” Jahquari said, “just come eat.”

Because what happened at Bar Casa Vale wasn’t just a bad night of service. It was a case study in how racism operates at work, how HR exists to shield management, and how quickly employers will punish workers who act in solidarity.

And it was a reminder that when workers leave together, when they refuse to accept violence, humiliation, and exploitation as the cost of survival, they expose the lie holding the industry together.

It was a reminder: when racism and exploitation are treated as normal business practices, workers walking out together is not the problem, but the solution.

Follow updates:

- Instagram: @madman_popup

- TikTok: @jahquari