Autonomy in Practice: Permanent Vigil’s and Sacred Fires

On the same day community members gathered to grieve the killing of Renee Good at the hands of an ICE agent in Minneapolis, something shifted in downtown Portland, Oregon. What began as a vigil and flag burning across from the federal courthouse transformed, almost organically, into an autonomous zone that held space through the night and reignited a conversation many people have been having quietly for months: What if mourning isn’t enough? What if we actually hold ground?

“What started as a permanent vigil just… grew,” one participant said. “People had yarn in their pockets and wrapped it around a corner of the park, and that became the seeds for the first barricade. Then folks were like, fuck it, and started dragging street barricades over. It all snowballed from there.”

Earlier that evening, a large rally had taken place at City Hall, organized by groups including DSA. Like many mass demonstrations, it drew a crowd, delivered speeches, and then… ended after an hour. People began to disperse. And as they did, frustration was audible.

“There were people literally walking away saying, ‘That’s it? That’s all we’re gonna fucking do?’” they recalled. “A lot of those same people ended up coming over where the flags were burning.”

Just a block away, others had already begun something different. A vigil was forming in Chapman Square, a park across the street from the federal courthouse. American flags were burned in protest. Candles and offerings appeared. Yarn was strung around a corner of the park, a small, almost symbolic boundary.

Then people who had just left the larger rally started walking over. They didn’t just watch. They joined.

More makeshift barriers appeared. Street materials were dragged into place. What had been described as a vigil quickly became a defended space. Not through a centralized call, but through a shared feeling: we can’t just march, go home, and wait for the next tragedy to listen to all the same speeches again.

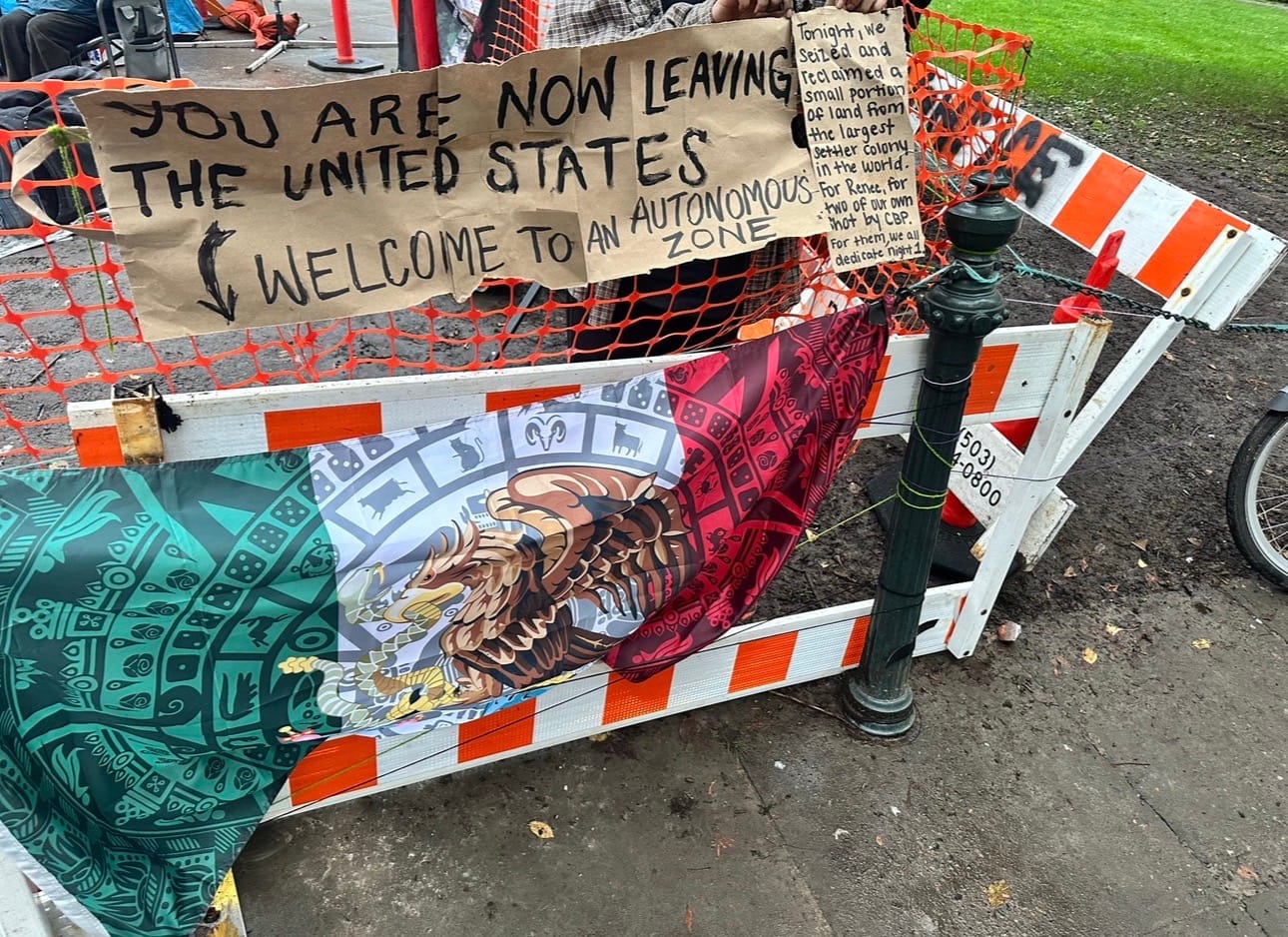

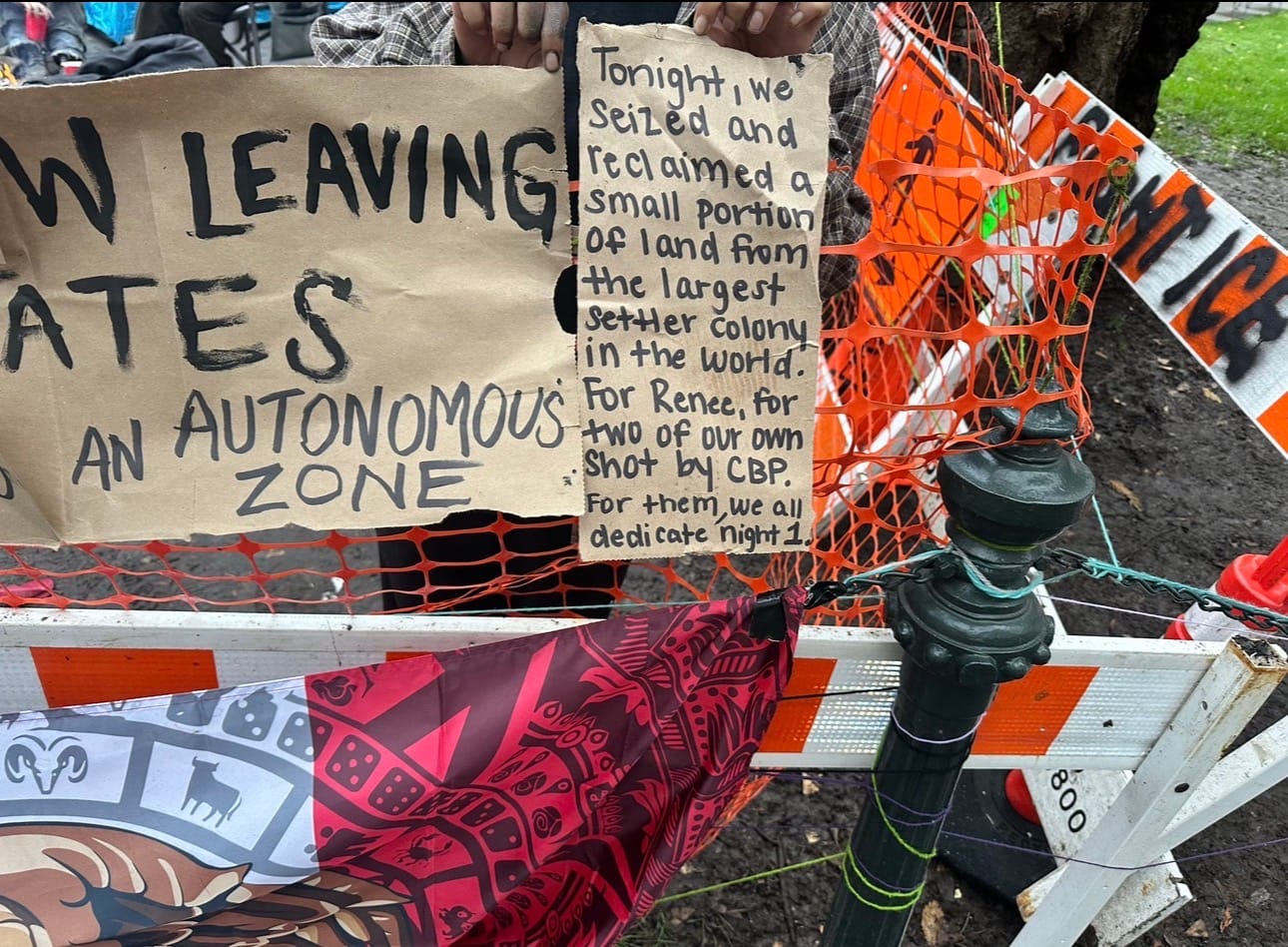

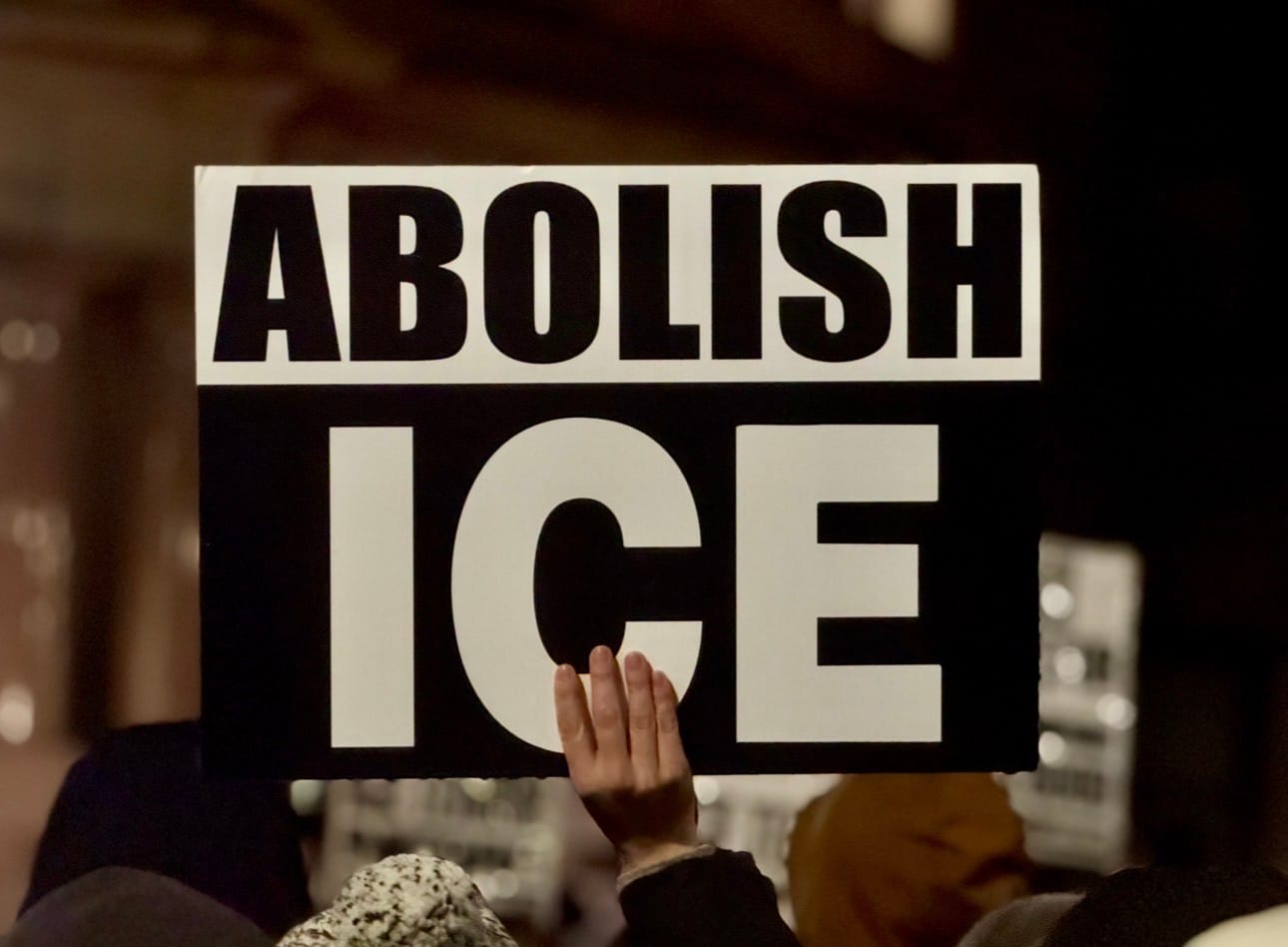

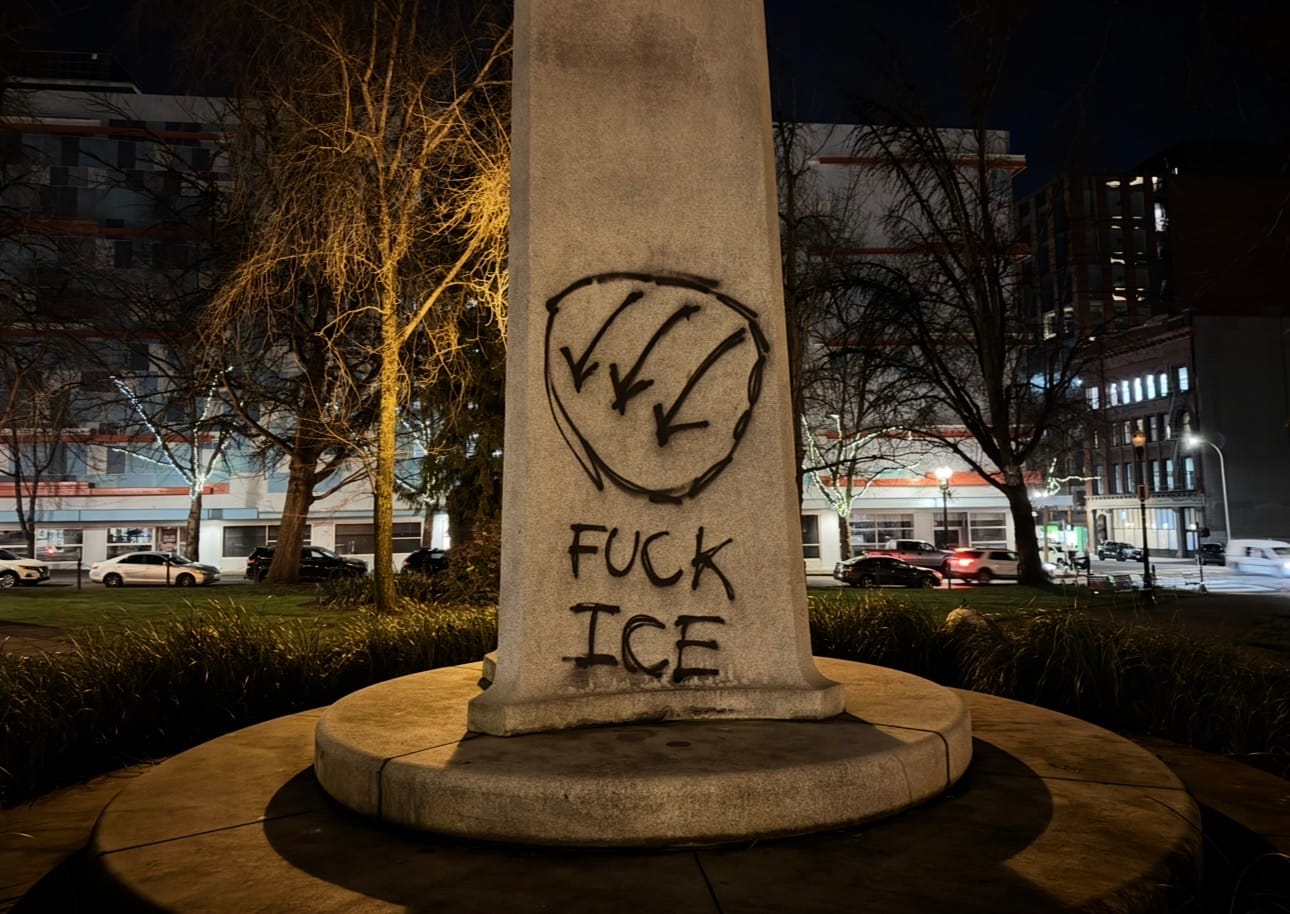

photos from the permanent vigil

“It was a rebellion,” they said. “Not just about Renee. It was about everything that led to her murder. It was people saying, we’re done responding passively.”

While Renee Good’s murder was the immediate spark, participants say the space was about more than a single event. It was about the cycle people are exhausted by… outrage, march, speeches, dispersal, repeat. All while the systems responsible for this violence remain untouched.

This time, instead of dispersing, people stayed.

Indigenous community members played a central role in establishing a sacred fire at the site, grounding the space in ceremony, remembrance, and resistance. People said this was also a way to honor earlier anti-ICE organizing that began in Portland in January 2025, when Indigenous community members held weekly sacred fires outside the ICE facility long before summer crowds grew.

That history often gets erased. This space made it visible again. “This was about honoring the people who paved the way.”

“It set an amazing tone,” the participant said. “You had Indigenous community members who don’t just show up when something’s trending. Their whole existence is resisting settler colonialism. Being in space with that guidance changed how people understood what we were doing.”

Photos of barricades at the vigil

The fire burned from around 8:30 p.m. until roughly 10 a.m. the next morning, the sacred fire burned for about 14 hours before police moved in at a moment when many supporters had gone to provide court support elsewhere. Participants say the timing was deliberate.

But it didn’t end there.

On January 9th, a few days after Good was murdered by ICE, Border Patrol shot Luis David Nino-Moncada and Yorlenys Betzabeth Zambrano-Contreras, a Venezuelan couple in Portland, Oregon. The sacred fire returned, this time in a location chosen with sharper political symbolism. The new site sat within view of the county jail (often called the “(in)Justice Center”), the federal courthouse, and City Hall.

“These institutions claim to represent justice. The fire was there to say otherwise.”

The second gathering expanded beyond vigil into political education and open discussion. People spoke not only about grief, but about responsibility, naming City Hall’s role in permitting the ICE facility, the courts’ role in deportation pipelines, and the broader illusion that these institutions are neutral.

“This time it was way more intentional,” the participant said. “The sacred fire represents truth. And it was surrounded by institutions of lies.”

At one point late in the night, a small group of right-wing agitators drove by and attempted to provoke people at the fire. Those present faced a choice: extinguish the fire to prevent harassment, or hold their ground.

They chose to stay.

The agitators eventually left. The fire kept burning.

For those there, the moment was symbolic of something larger: when people remain rooted together, especially under Indigenous guidance and ceremony, intimidation loses some of its power.

Participants drew connections between the autonomous zone and other forms of repression in Portland, especially police harassment of mutual aid groups and community resource distros. In those cases, simply feeding people or existing in shared public space has drawn heavy police presence and legal threats.

To many involved, the message from the state is clear:

Autonomy itself is what’s criminalized.

In that context, defending a vigil, holding a sacred fire, and refusing to disperse becomes more than symbolic. It becomes a direct challenge to who is allowed to occupy land, make decisions, and care for community outside state control.

Both nights of the autonomous space coincided with other actions happening across Portland, including large demonstrations at the ICE facility. With multiple events unfolding at once, police resources were stretched thin. Participants say that mattered.

It was a reminder of an old movement lesson: authorities can easily manage one large, predictable protest. They struggle when resistance becomes decentralized, simultaneous, and self-directed.

People came to mourn Renee Good. They stayed because mourning alone felt like surrender.

What emerged downtown wasn’t a perfectly planned occupation or a pre-announced autonomous zone. It was something messier and more alive: a community deciding, in real time, not to go home.

And in that decision, to hold a fire, to defend space, to gather under Indigenous guidance, to speak openly about the failures of local institutions, many participants say they glimpsed something that felt less like protest and more like practice.

Not just responding to violence.

But rehearsing a world beyond it.